Juneteenth

Why is Juneteenth such an important celebration? Join us for a look at the history and legacy behind this increasingly significant date.

The Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, as the nation faced a third year of civil war. It declared that all slaves within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” It was a turning point in the war, making the battle for human freedom a key focus.

However, enforcement of the Proclamation depended on a Union victory, and as the war raged, many slave owners had moved west to Texas, far from Union lines. Slaves far from Union-held territory had no way to know they were free.

The Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for the Thirteenth Amendment, outlawing slavery, passed April 8, 1864. It was not until Dec. 18, 1865, with the war over, that the necessary three-quarters of the states ratified the Amendment, ensuring forever that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude … shall exist within the United States.”

The Proclamation also announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union forces, and by the end of the war, about 180,000 Black soldiers and sailors (10% of the Union forces) had fought for the Union and for freedom. Nearly 40,000 died over the course of the war, most from disease.

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.“ — Frederick Douglass

Provost Guard of the 107th Colored Infantry, Fort Corcoran, Washington, D.C., 1863

The First Juneteenth: 1865

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.”

— General Orders Number 3, Headquarters District of Texas, Galveston, June 19, 1865

On June 18, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger, with 2,000 soldiers, landed at Galveston to occupy Texas. The next day, he announced from the balcony of the Ashton Villa that the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation was finally in force in Texas.

So it was not until the war was over that hundreds of thousands of Texas slaves were free. Celebrations broke out at once, and this was how Juneteenth began.

It is different from Emancipation Day, which celebrated the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth, since it marked freedom for all, is often called Freedom Day.

Juneteenth has been celebrated since 1865, often featuring communal meals, as in 1889 at Cleburne, TX., where people “met at the grove to enjoy a basket dinner and barbecue.” The celebration grew in the late 20th century, with Texas making it an official state holiday in 1980.

Each year more neighborhoods and cities have launched festivities to celebrate freedom and mark the achievements of African Americans during and after slavery.

Emancipation Day in Florida

Juneteenth is now celebrated in many states, but it took a while to catch on in Florida, where people have long marked a different Emancipation Day.

In 1865, with the war ending, many telegraph lines were destroyed, and news traveled slowly. No-one really knew the war was over until Union troops arrived to accept Confederate surrender. The further west you lived, the longer the news took.

In Florida, General Edward M. McCook arrived in Tallahassee to receive the surrender on May 10. On May 20, he announced the Emancipation Proclamation from the steps of the Knott House, ending slavery in Florida. Thus many Floridians celebrate May 20 as Emancipation Day.

In Tampa, freedom came earlier. Enslaved people were liberated by Union troops, May 5-6, 1864, when they captured Fort Brooke. Tampa has often held Emancipation Day celebrations May 5 or 6.

“As a child growing up rural in Leon County, we always celebrated Emancipation Day May 20. Schools were dismissed and around 3 p.m., families would gather at the church. The celebration began, always, with prayer and thanks to God for our freedom. After which, onto the church grounds for the celebration.

The women would cook all day and brought food that was shared by all — fried chicken, fried fish, old fashioned potato salad, fresh greens, sweet potato pies, jelly layered cake, chocolate, and coconut layered cakes. The men made big old barrels of cold lemonade.

We celebrated our freedom. The elders and young men beat the drums in a beat unlike any I have heard, but it represented the sounds of freedom.”

— Gloria Jefferson Anderson, Florida Memory Project

Post-Emancipation: Jim Crow

In 1868, Amendment XIV of the Constitution had given African-American men full citizenship and promised equal protection under the law. Blacks voted, won elected office, and served on juries. But 10 years later, federal troops had withdrawn from the South, and the Republican Party, champion of Reconstruction, had fallen from national power. Over the next 20 years, Southern Blacks lost almost all they had gained, as Jim Crow laws — state and local statutes that legalized segregation — effectively served to return the South to its pre-war class and racial structure.

Why “Jim Crow?”

In 1868, Amendment XIV of the Constitution had given African-American men full citizenship and promised equal protection under the law. Blacks voted, won elected office, and served on juries. But 10 years later, federal troops had withdrawn from the South, and the Republican Party, champion of Reconstruction, had fallen from national power. Over the next 20 years, Southern Blacks lost almost all they had gained, as Jim Crow laws — state and local statutes that legalized segregation — effectively served to return the South to its pre-war class and racial structure.

The Black Codes

The roots of Jim Crow lie in the Black Codes — laws that began in the South right after emancipation. The first Codes detailed when, where and how freed slaves could work, and for how much money. Their intent was to put Black citizens into servitude, remove voting rights, and control movement. The codes worked along with labor camps, where incarcerated prisoners were treated as slaves.

Violence and the Ku Klux Klan

Supported by Jim Crow laws, local government and the Democratic Party fought efforts to help freed slaves progress, enabling a culture of violence to flourish. Black schools were vandalized, and families were attacked, murdered, and forced off their land.

The KKK, born in 1865 in Pulaski, TN, as a private club for Confederate veterans, grew into a secret society, terrorizing Black communities, with members at the highest levels of government.

KKK parade in Binghamton, NY, 1920s, at a time when Klan membership exceeded 4 million.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Living under Jim Crow

Jim Crow laws enforced segregation in all public spaces in the former Confederate states, starting in the 1870s. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson ruling upheld them, by requiring “separate but equal” treatment.

This doctrine was extended to public facilities and transportation — in practice, accommodations for non-Whites were consistently inferior, underfunded, or even non-existent. Legalized segregation principally existed in the South, but elsewhere it was maintained through housing regulations, bank lending-practices, and employment discrimination. The U.S. military was already segregated; Pres. Woodrow Wilson, a Southern Democrat, initiated segregation of federal workplaces in 1913.

Segregation of public schools was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, and the Jim Crow era legally came to an end with the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Examples of Jim Crow Laws

It shall be unlawful for a negro and white person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards or dice, dominoes or checkers. — Alabama, 1930

Marriages are void when one party is a white person and the other is possessed of one-eighth or more negro, Japanese, or Chinese blood. — Nebraska, 1911

No colored barber shall serve as a barber to white women or girls. — Georgia, 1926

It shall be unlawful for any white prisoner to be handcuffed or otherwise chained or tied to a negro prisoner. — Arkansas, 1903

The Corporate Commission is hereby vested with power to require telephone companies in the State of Oklahoma to maintain separate booths for white and colored patrons. — Oklahoma, 1915

The segregated Rex Theatre in Leland, Mississippi

Marion Post Wolcott/Library of Congress/Getty Images

Jim Crow in Florida

Florida enacted some of the most severe Black Codes in the South and was among a few states to enshrine Jim Crow laws in its Constitution. Felony disenfranchisement laws, coupled with “vagrancy” laws (punishing Black people for being unemployed) were intended to permanently disenfranchise Blacks. Convicted “vagrants” would be “lent” to farmers to work free for a year — in practice a return to slavery.

Later, Florida was one of the most dangerous states for Blacks in the Jim Crow era, with the highest number of lynchings per capita. Some Jim Crow laws were in effect until the state’s current Constitution was passed in 1967.

There were safe havens, such as Paradise Park, which opened in 1949 as the “colored only” counterpart to the popular Silver Springs, just a mile down the Silver River near Ocala.

Paradise Park, Ocala, 1950

University Press of Florida

Florida Jim Crow Examples: 1885-1967

-

All courtships between a white person and a Negro person, or between a white person and a person of Negro descent to the fourth generation inclusive, are hereby forever prohibited. (State Constitution, 1885)

-

Separation of races required on all streetcars. (Statute, 1905)

-

Criminal offense for teachers of one race to instruct pupils of the other in public schools (Statute, 1927).

-

Races segregated on public carriers (Statute, 1958)

-

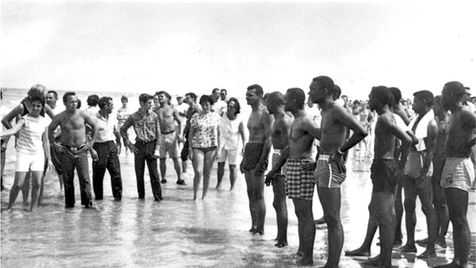

Whenever members of two or more races shall be upon any public … bathing beach … it shall be the duty of the Chief of police or another … to clear the area involved of all members of all races present. (Sarasota City Ordinance, 1967)

Amazing Young African Americans!

In more than 150 years since Emancipation, African Americans have gone on to spectacular success, many at a young age. We showcase a few outstanding 21st century achievers, an inspiration for us all.

Jewell Jones

In 2016, Jones became the youngest person ever elected to the Michigan House of Representatives, at the age of 21. He was still studying political science and business at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, graduating in 2017. A political and community activist since childhood, he was elected to the Inkster City Council in 2015. As a politician, he says “There’s a lot of opportunity to do really great things.”

Anala Beevers

Born in New Orleans, Anala learned the alphabet at four months old, and by 18 months she could recite numbers in Spanish and English. At 5 years old, in 2014, she was accepted into the Mensa Society, the exclusive club for people scoring at the 98th percentile on an IQ test.

Stephen R. Stafford

From Lithonia, Georgia, Stephen graduated in 2015 from Morehouse College at age 17, with a triple major in pre-med, mathematics, and computer science. He went on to Morehouse School of Medicine and hopes to graduate by the age of 22.

“I want to live up to my potential. Potential doesn’t have a limit. It’s like a rainbow. You can constantly keep chasing it and you will never get to it. And I don’t have any limits as long as I keep trying.”

— Stephen R. Stafford